Visitors — A Poem, in want of Music

An open gate, an invitation —

sleek bodies gleam

in pale moonlight;

Beneath the arch

and past the vines,

they slip over the lawns.

a silver mist upon

my eyes —

I miss their call

Softly, they tread

on slender limbs

light steps chime like distant bells;

Their heads are crowned

in bones and velvet

starlight gilds their movements.

I drift, I sleep,

a silver mist upon

my eyes —

I miss their call

Gentle the heart,

quiet the tongue,

observe the drifters as they pass;

Extend the bough,

bestow the bloom, and

spread a cloth in welcome

Alert me, wake me

to their swift darkling arrival —

and together, we shall dream…

–C.Birde

Wisteria — A Haiku

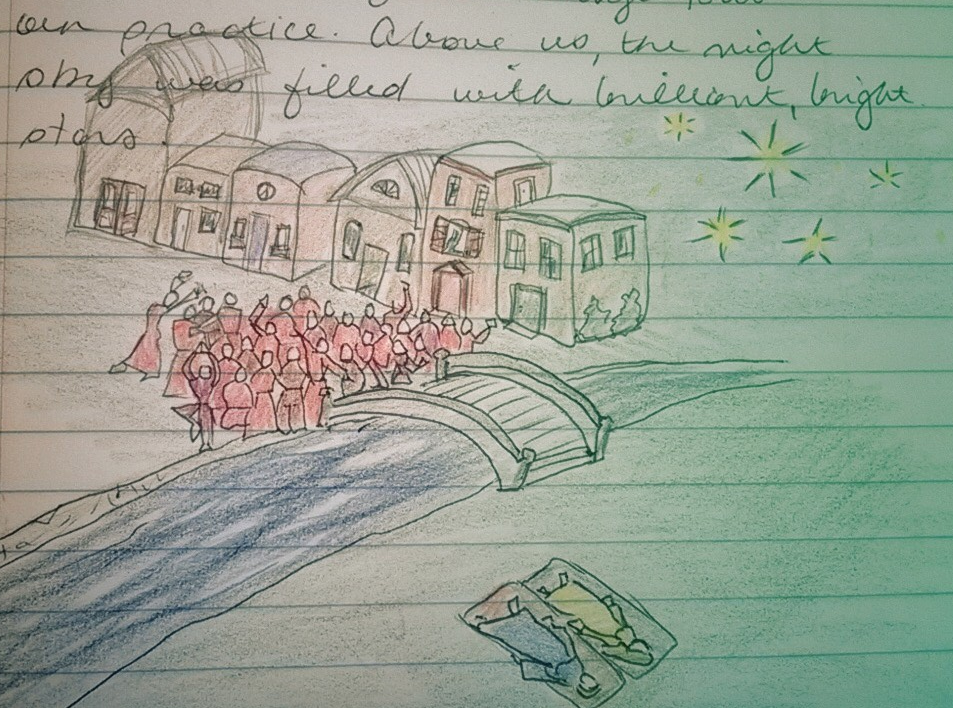

The Far Side — A dream

This ancient city is thick with people tonight. They move through its narrow streets and hairs’ breadth alleys slowly, like a flood tide. The throng’s collective voices, lapping one over another, are a steady drone of sound. Not a word is decipherable. Old buildings lean against one another, crowding up against the streets’ edges to observe in silence as the human river inches by.

We are not surprised by the crowd, as this is a night of singular celebration. But my senses are overwhelmed. The constant hum of noise is a vibration so palpable, I feel it in my skin. Everywhere I look, the people are clothed in subtle shades of shifting red, and they move ceaselessly in the darkness; their bodies press so close, I can scarcely tell myself from any other. My mother and I are squeezed to the margins, pushed backward away from the mass until we find ourselves forced across a low stone bridge that stretches over a canal. The dark water moves slowly, slips easily between its banks and on its way.

At the far side of the canal, there is a calm silence. The grass is thick and damp and empty of people. Here, in this quiet space, my mother and I are able to spread our mats. We lie down on our backs and look up at a vast, dark sky illuminated with countless bright stars.

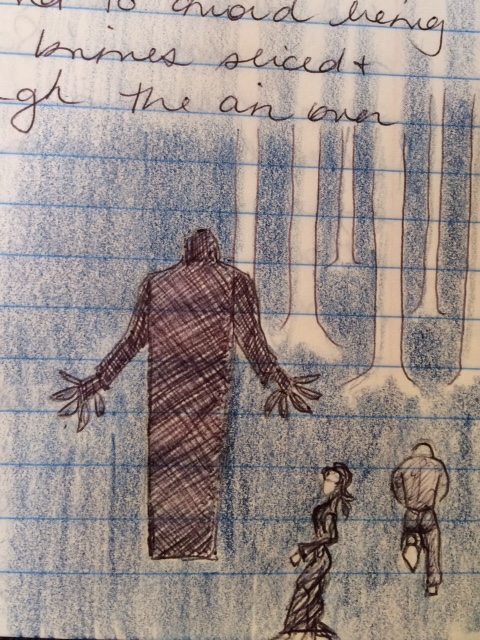

Duck Dog — A Dream

The forest here is peculiar — the slim trees arranged evenly in rows by some grand design so that one might move easily between them in all directions. They have no branches until about 20 feet up. And in spite of the late hour and moonless sky, their smooth trunks reflect dim light from some unknown source. They cast long, straight shadows in a measured grid over the flat, dark earth.

Half a dozen or so men line this odd forest’s edge. They are extraordinarily tall, reaching seven feet in height. Great black, mantled trench coats swath them from shoulders to feet. The men’s faces in deep shadow that the trees’ dim glow cannot penetrate. With slow, sweeping gestures, the dark men indicate a path through the trees. Silently, they entreat us to come, to see the ‘duck dog’.

Some of those gathered with me beyond the perimeters of both men and trees begin to wander off in the direction of this promised creature, but they so do in a dispirited fashion, as if compelled. Their steps drag, their shoulders are hunched and their heads are bowed. The line of dark men parts to admit these poor folk who trudge forward through the softly gleaming trees.

Soon, I am alone, crouching at the edge of this scene. It seems only I am alert and attentive enough to notice the dark men’s oddly-shaped hands –a flat rectangular object is adhered to each of their great palms, and from each palm protrudes five slim lengths that mimic fingers but simply cannot be such digits. Continuing my surveillance, I realize, with a shock, that each shadowy man holds a sheath of throwing knives. The ‘duck dog’ is a trap. The men are luring us into the woods for slaughter.

I raise an alarm. I call and shout to warn the others to no avail — my subjugated companions continue dragging their steps forward, sloping off between the rank of dark men into the trees. My appeals, however, have drawn the unwanted attention of the dark men themselves. Their heads swivel toward me in unison — I have been marked as a target for elimination. Suddenly, the air is alive with noise and motion as the men hurl their flashing knives. I hear the sleek weapons hiss pass my head to bury themselves into earth and tree trunks alike. Diving to ground, I duck the paths of these deadly projectiles. As I lay upon the cool earth in the leaf litter, I suspect that the ‘duck dog’ was not a creature, but a warning.

Lilac Memory — A Poem

Rabbits and Heart’s Land — A Truth

In the sixth grade, when my peers were preoccupied with dating, dances, and first kisses, I was busy modifying the  cardboard pencil box stowed in my desk to create a rabbit warren. This was, you must understand, the next obvious step after having made the rabbits — they would need a place to live, after all. I had made the rabbits by twisting the pink, cylindrical erasers off the tops of two pencils. Their fronts bore little smiling ink faces; their backs tiny tails; and I had cut small, precise ellipses of paper and taped these in place to serve as ears. Naturally, their names were Peter and Benjamin. They had very full lives, complete with rabbit-centric adventures, which led to their ultimate discovery. My teacher eventually noticed my distraction, my hands animatedly occupied within the shadowed, rectangular recess of my desk. I was a good student and generally quiet, so I merely received a raised eyebrow as reprimand. (This was enough.)

cardboard pencil box stowed in my desk to create a rabbit warren. This was, you must understand, the next obvious step after having made the rabbits — they would need a place to live, after all. I had made the rabbits by twisting the pink, cylindrical erasers off the tops of two pencils. Their fronts bore little smiling ink faces; their backs tiny tails; and I had cut small, precise ellipses of paper and taped these in place to serve as ears. Naturally, their names were Peter and Benjamin. They had very full lives, complete with rabbit-centric adventures, which led to their ultimate discovery. My teacher eventually noticed my distraction, my hands animatedly occupied within the shadowed, rectangular recess of my desk. I was a good student and generally quiet, so I merely received a raised eyebrow as reprimand. (This was enough.)

Rabbits often figured into my solitary play. I spent many hours during the Summer as a rabbit. As such, I made my home beneath the arching branches of a Spiraea in my family’s back yard. The soft, green oval leaves of bush honeysuckles provided the mainstay of my make-believe rabbit diet, supplemented by both the roots and flowers of Queen Ann’s Lace, and the ‘bird berries’ (also from the bush honeysuckle) which my parents had warned against ingesting, having explained their poisonous nature. While scampering through Summer in this guise, I called myself Cottontail.

Certainly, you’ve noticed the common thread between these two activities, and you’d be right to conclude that the works of Beatrix Potter greatly influenced the imaginative diversions of my youth. Beatrix Potter was a remarkable woman well ahead of her time — author, illustrator, patent-holder, natural scientist, and conservationist. Naturally, during our recent travels through England, my husband and I included Ms. Potter’s home in Near Sawrey, Lancashire, on our itinerary of Literary Figures’ Homes to See.

Visiting Hill Top Farm was like walking through the pages of Beatrix Potter’s many little books — along the winding slate path  that would, as Spring advanced, soften with wildflower beds and hum with bees and butterflies.

that would, as Spring advanced, soften with wildflower beds and hum with bees and butterflies.  Past ivory ewes and new lambs that lay contentedly beneath a twisting tree in a neatly fenced grassy sward. Pausing at the scrolled, moss-green iron gate to see the garden — filled with rhubarb and geraniums and the weathered tin watering can that must certainly have been the site of Peter Rabbit’s trials. And within her home, the entrance hall with its large kitchen range; the crimson-carpeted stairs and Grandfather clock ticking on the landing; in a small, spare bedroom, the dollhouse of her childhood that served as the home of Two Bad Mice.

Past ivory ewes and new lambs that lay contentedly beneath a twisting tree in a neatly fenced grassy sward. Pausing at the scrolled, moss-green iron gate to see the garden — filled with rhubarb and geraniums and the weathered tin watering can that must certainly have been the site of Peter Rabbit’s trials. And within her home, the entrance hall with its large kitchen range; the crimson-carpeted stairs and Grandfather clock ticking on the landing; in a small, spare bedroom, the dollhouse of her childhood that served as the home of Two Bad Mice.

Beatrix Potter’s passions and talents echo throughout her home, and her surroundings are reflected in her stories. Experiencing Hill Top first hand, this positive feedback loop between location and artist is beautifully obvious. Equally so was my response — the immediate announcement that I should like to move in. There are places that call to us, places that beckon and sing within our veins like heartbreak when we find them. My heart sang with recognition on Beatrix Potter’s doorstep.

Act of Love — A Truth

We had tarried too long at Sissinghurst. How could we not have? Anyone would lose track of time wandering the grounds of  the once-home of Vita Sackville-West and Sir Harold Nicolson. And my husband and I had done so. Our quick visit had become hours long. But we must be forgiven. Drifts of sunny daffodils swayed in the unmown lawns. Shy bluebells and checkered fritillaria crowded against worn brick walls. Formal gardens invited a stroll, then a pause, then a continued, sustained linger. And we had so lingered. Including at that moment — after climbing the worn stone, spiraling steps of the Elizabethan Tower — when we had emerged once more into open air high above.

the once-home of Vita Sackville-West and Sir Harold Nicolson. And my husband and I had done so. Our quick visit had become hours long. But we must be forgiven. Drifts of sunny daffodils swayed in the unmown lawns. Shy bluebells and checkered fritillaria crowded against worn brick walls. Formal gardens invited a stroll, then a pause, then a continued, sustained linger. And we had so lingered. Including at that moment — after climbing the worn stone, spiraling steps of the Elizabethan Tower — when we had emerged once more into open air high above.  The grounds were laid out below us from this greater vantage point in an organized loveliness. It was windy, the gusts pulled at my hair; and the air was filled with vaguely unfamiliar birdsong. Truly, we enjoyed the beauty and architecture of the Castle and gardens. But I must admit, I would not have known of Vita’s home if it had not been for my deep appreciation of Virginia Woolf’s writing. For Virginia’s novel Orlando, one of my favorite books, was inspired by Vita and Harold’s Sissinghurst Castle, and this, in turn, had inspired my desire to visit.

The grounds were laid out below us from this greater vantage point in an organized loveliness. It was windy, the gusts pulled at my hair; and the air was filled with vaguely unfamiliar birdsong. Truly, we enjoyed the beauty and architecture of the Castle and gardens. But I must admit, I would not have known of Vita’s home if it had not been for my deep appreciation of Virginia Woolf’s writing. For Virginia’s novel Orlando, one of my favorite books, was inspired by Vita and Harold’s Sissinghurst Castle, and this, in turn, had inspired my desire to visit.

Miles pass differently in England. The country roads twist and climb, drop then narrow. The landscape rushes past, alternating between swells of green fields, antique hedgerows, and worn brick or field-stone walls. More than occasionally, one quite literally drives past someone’s doorstep. We took care to be considerate visitors as we drove south. We had time — my guide book clearly stated that Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s summer home in Rodmell allowed visitors entry until 5:15pm. As we drew closer to our destination, the roads became hillier, rougher, narrower, more difficult to navigate. But we arrived with time to spare and even found parking — no small feat in itself.

I can only describe myself as having been elated. We walked a short distance along a remote and dusty country road toward Virginia Woolf’s. We passed houses that huddled shoulder-to-shoulder and spilled with ivy and gardens and tree shadow. The entrance to the summer home of Virginia and Leonard resembled an old garage built into a retaining wall beneath the house and grounds. We entered to purchase our tickets, and the gentleman at the desk, while smiling, told us that sadly, we could not enter the house. I thought I had not heard him properly. The time clearly showed 4:45pm. The gentleman apologized — he seemed genuinely sincere — but our book must contain a misprint. He encouraged us to enjoy the gardens, which remained open till dusk.

I think that at that moment, if I had been struck, I would have rung hollow and ghostly as a distant bell. I felt neither anger  nor sorrow, but rather a sense of disconnect, a sense of being untethered. I followed my husband out of the shop and we edged along the road, then up the steps and through a wrought iron gate. We walked past a small garden with a pool over which tiny insects skimmed and swirled, past a stone statue of a young woman. Our steps sounded along the walk that bordered the house, then bent sharply around a compact greenhouse that jutted from the house itself. Virginia Woolf had had a greenhouse — the thought had hovered about my head without a place to rest. When my husband stood in front of the greenhouse door, when he laid his hand upon and then turned the handle, I had simply watched as if from a great distance. When he descended the steps to the door of the house itself, I came to — “But it’s closed,” I said. His response was, “Do you want to see her home or not?”, and then he turned the handle of that second door and it had swung open to admit him.

nor sorrow, but rather a sense of disconnect, a sense of being untethered. I followed my husband out of the shop and we edged along the road, then up the steps and through a wrought iron gate. We walked past a small garden with a pool over which tiny insects skimmed and swirled, past a stone statue of a young woman. Our steps sounded along the walk that bordered the house, then bent sharply around a compact greenhouse that jutted from the house itself. Virginia Woolf had had a greenhouse — the thought had hovered about my head without a place to rest. When my husband stood in front of the greenhouse door, when he laid his hand upon and then turned the handle, I had simply watched as if from a great distance. When he descended the steps to the door of the house itself, I came to — “But it’s closed,” I said. His response was, “Do you want to see her home or not?”, and then he turned the handle of that second door and it had swung open to admit him.

I am not a rule-breaker by most accounts. I was raised to respect authority, to adhere to expressed guidelines. I am often unhappy about this. Deeply discontented. It is so hard to break free of our conditioned roles. To allow ourselves to be and do something ‘ other’. Even if it is a thing so small that the most it might earn is a raised eyebrow or a stern reprimand. Often, such things are easier to manage with an accomplice. My husband knows me well, and at that moment he fully understood my heart’s desire. When he opened that door, when he entered Virginia’s summer home, I was suddenly very truly present in my skin. No longer was I untethered. And I can say, with some infinitesimal measure of rebellion, that I followed.

other’. Even if it is a thing so small that the most it might earn is a raised eyebrow or a stern reprimand. Often, such things are easier to manage with an accomplice. My husband knows me well, and at that moment he fully understood my heart’s desire. When he opened that door, when he entered Virginia’s summer home, I was suddenly very truly present in my skin. No longer was I untethered. And I can say, with some infinitesimal measure of rebellion, that I followed.

We were met almost instantly by a young woman — a docent sent to Rodmell only recently. It was her third day. She was very happy to show us the living areas downstairs. We stepped in Virginia’s footsteps. We touched the chair she had once sat in. We trailed fingers over the small table that her sister, Vanessa, had decoratively painted. Or maybe, only I did this, and my husband watched. Our guide pointed out the fireplace in the small living room, the letters open upon the desk, the chairs in the dining room, and the painting of Virginia (also by Vanessa) on the wall above the vase of fresh daffodils. She left us alone to breathe the rarefied air.

We did not overstay our welcome. But when we left the little house, I was able to enjoy the gardens as I would not have been able if my small wish had remained thwarted. I was able, then, to look upon the separate structure that contained Virginia Woolf’s actual writing desk and chair and typewriter and glasses with a contentedness I might not have otherwise been able to enjoy. All thanks to an act of surrogate bravery on my husband’s part. A small act to some, perhaps; but most definitely an act of love.

Spring — a poem

At last —

dormant, minimalist Winter

releases His grip on the Earth,

and Spring slowly awakens,

tests the air,

breathes.

She stretches twiggy,

bud-tipped fingers.

She tosses Her leafy head,

shakes out Her skirts

of grass and wildflowers

and smiles in birds’ wings.

But mostly, She laughs —

a laughter that perfumes the air

and saturates ear and eye.

And I —

giddy, delighted, drowning,

laugh with Her.

–Carrie Birde

Changes — A dream and a truth

Changes — the dream

I stand on my front porch. The windows reach from floor to ceiling, and each pane of glass frames a view — sparrows in the dormant hedge; white picket front gate; the upward twist and thrust of linden’s trunk. The day is bright, yet gray, and the trees are just beginning to consider putting out leaf buds, for though it is spring, the air remains quite chill. Beyond our porch, past our small square of yard, a man walks down the middle of the road. His head is bowed against the cold, his shoulders shrugged forward beneath his flannel shirt, and his hands are stuffed deep into his pants pockets. He walks toward our neighbors’ house, climbs the porch steps, knocks on front door. Our neighbors answer, and I can see they engage in brief conversation. Before the visitor departs, hugs are exchanged. Soon, I see another man, then another and another. They all do the same. Each one wanting to say goodbye to our neighbors, who have put their house up for sale and are moving.

Changes — the Truth

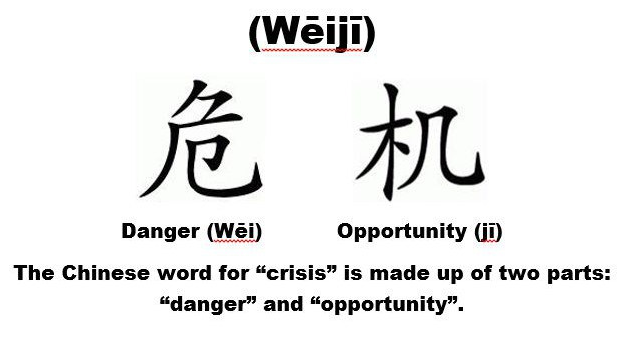

Our neighbors truly are moving. Their planned departure has become the most recent symbol to me of change. We hear so much of change — change is good, change is inevitable, change is the only constant. I have always found these descriptions uncomfortable, ill-fitting. The latter two seem fatalistic — as though we are simply the victims of change and have no say in the outcome; and the first one is so subjective — dependent entirely upon who is making the change, and who will receive the results of the changes. But several years ago, I saw a card that contained the Chinese ideogram for change along with the explanation that this tumultuous, heavy word, when written in Chinese  characters, is made up of two different words — danger and opportunity. Change contains danger and opportunity…This, I find easier to accept, that when the inevitable changes come our way, we have the opportunity to choose how we will confront them — as occurrences to be denied and struggled against, or as opportunities to search for some positive and unseen outcome.

characters, is made up of two different words — danger and opportunity. Change contains danger and opportunity…This, I find easier to accept, that when the inevitable changes come our way, we have the opportunity to choose how we will confront them — as occurrences to be denied and struggled against, or as opportunities to search for some positive and unseen outcome.

After thirty years, our neighbors have decided it is best that they downsize and begin the next chapter of their lives together. I cannot argue with their logic. They have always been been kind, generous, and gracious, and our neighborhood has benefited greatly from their presence. And though I have lost the card with the Chinese character for Change, I know that while I will miss our neighbors, I have now opportunities before me, only some that I can immediately envision — the opportunity to welcome new neighbors into our little community, to keep the tone of warmth and friendliness our former neighbors have set, and to hope we can expand the idea of neighborliness together.