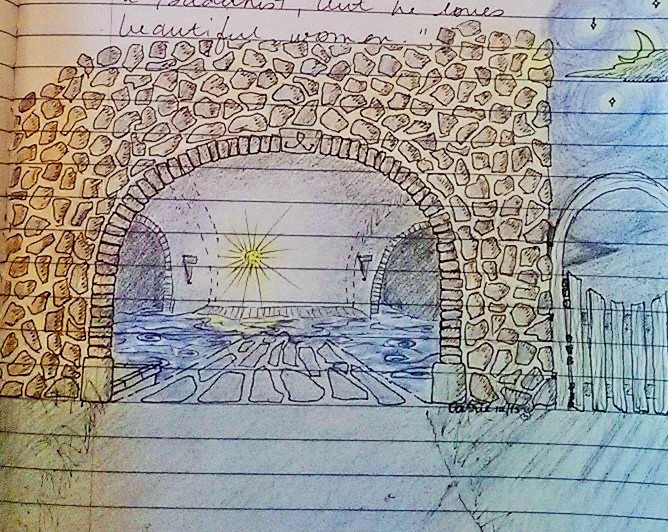

Buffeted by wind, the dirigible sails low over a serpentine river, banking left, then right, back and forth. It swings over the river’s ever-changing course, shouldering its way forward. Low stone bridges span the waterway at evenly-spaced intervals. When the craft approaches one, it must veer sharply upward to clear the structure. Engines churn, grind loudly as it strains to climb. Tail fins drag, sending up plumes of water. And we few inside are tossed about in half-light. Without seat belts, the ride is nerve-wrackingly bumpy. Pitched forward as the craft begins a steep ascent, I dig nails into the edges of my seat, hold on tight.

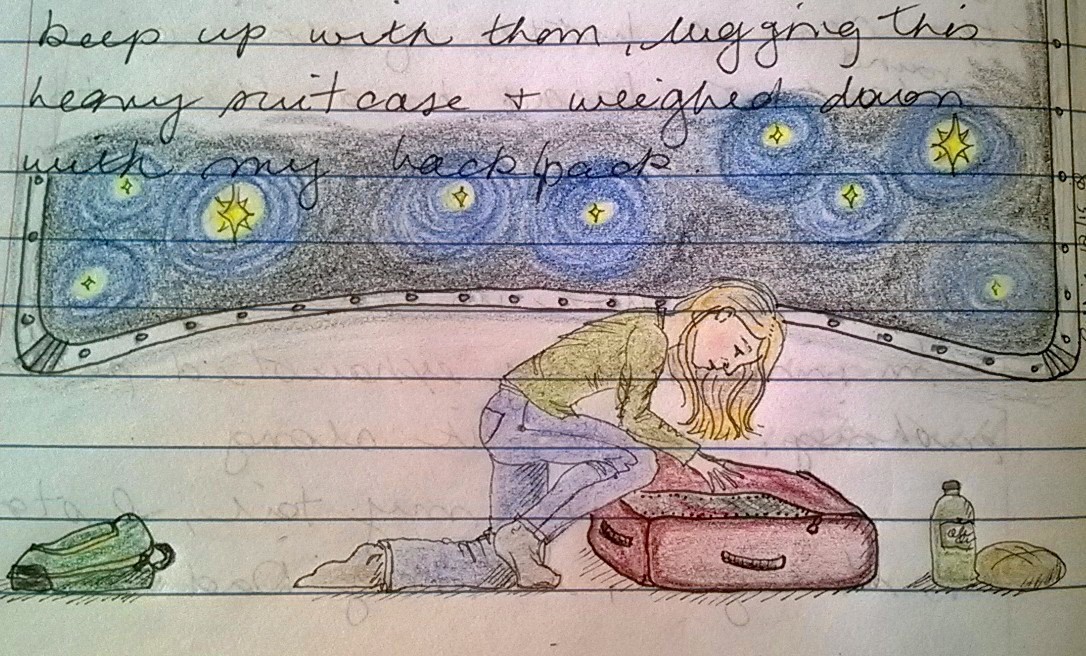

When at last, we dock, I rise from my bench to follow the others through the dirigible’s interior. Stepping over stiff, slim structural beams, we tread the craft’s taut and toughened skin. The line slowly inches forward, each person pausing to slip their ticket into a squat turnstile’s slot. Time after time, the turnstile’s polished arms clunk and rattle as a rider pushes through. The last in line, I realize my ticket is too large, does not fit into the slot. I fold my thick, fibrous ticket in half, in half again, then mash and force feed it into the too-narrow opening. It is slowly, grudgingly swallowed.

Bright daylight without. Squinting, I follow a neat gravel path that winds past a small peak-roofed kiosk. As I pass, a uniformed woman seated within this cramped structure waves me over. I approach, stand outside to peer into the small, smudged window.

“That will be $30,” the woman informs me. She doesn’t lift her head — all I can see is the flat top of her navy blue hat. The hat’s stiffened black brim flashes with reflected light. She scribbles ceaselessly in a small pad.

I explain the misunderstanding — I had a ticket. Too large; didn’t fit.

“Thirty dollars, please,” she firmly repeats, interrupting me. Still, she does not lift her eyes to meet mine, continues writing in her pad, filling out her form.

Frustrated, I insist I would only have had a cup of tea and eaten one-and-a-half pancakes, had either been offered. The round tip of her nose protrudes from beneath her cap’s rim as, head down, she completes her form. She tears a yellow carbon-copy sheet from the little pad, hands it to me. I have been charged the full amount. Thirty dollars. Five pancakes worth.